Synthetic Rifle Stocks

An Abbreviated History

feature By: John Barsness | July, 20

The development of what are generically called “plastics” began in the mid-nineteenth- century, when the long molecules of cellulose – abundant in plants – were treated to form various polymers used in products from camera film to billiard balls. Traditionally, billiard balls were made of elephant ivory, but the popularity of billiards kept increasing while the supply of elephants kept decreasing. In 1869, a New York chemist named John Wesley Hyatt developed a suitable polymer – which could also be shaped into various other items normally made from animals and plants, including cloth fibers.

In 1907, another New York chemist, Belgian-born Leo Baekeland, developed a totally synthetic plastic named Bakelite, which could be molded for mass production. Initially, Bakelite was developed as an electrical insulator but ended up being used for thousands of products, including telephone bodies, toys, kitchen bowls and plates. It was also used on firearms, though usually for handgun grips as it was too brittle to take much recoil.

As plastics continued to evolve, several became more suitable for stocks. Among the early synthetic-stocked long guns was the Stevens .22 Long Rifle/.410 combination gun, with a buttstock and forend made of Tenite, a tougher plastic made from softwood cellulose. Produced from 1939 to 1950, the Stevens was adopted as a survival gun by what was then the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War II. This may have influenced the 1963 adoption of the first synthetic-stocked U.S. military rifle, the Armalite Model 15 – officially designated the Rifle, Caliber 5.56mm, M16 – with stocks made of a composite resin similar to that used in billiard balls.

Remington was the first major manufacturer to introduce synthetic stocks on sporting rifles, in 1959 introducing its nylon-stocked Model 66 semiauto .22 rimfire. Nylon was developed in 1935 by DuPont, but the name was never trademarked, so Remington used the modernized name Nylon Zytel-101. (The U.S. was then heavily involved in the Space Race with the Soviet Union, and many marketers attached space-age sounding names to products.) At first, many shooters resisted the idea. After a co-worker bought a 66, my father later went on a mild rant in the privacy of our home, saying rifles had “wood” stocks.

Early synthetic stocks were made by molding heated plastic, but another technology appeared after World War II, borrowed from the boat industry, epoxying layers of fiberglass cloth inside a mold to make a thin but strong shell. This was used to make “lay-up” stocks, with the fiberglass/epoxy shell often filled with light plastic foam. Soon afterward, shooters started epoxying metal “pillars” inside the action screw holes to keep the thin-shelled stocks from collapsing as the screws were tightened. (Mauser had previously used steel pillars in the wood stocks of military rifles, but to allow screws to remain tight as the wood shrank or expanded.)

Lay-ups first became popular among hunters and benchrest shooters, who valued not only their stability compared to hygroscopic wood, but their light weight. Hunters used lay-ups to make “mountain rifles” carried in steep country. Lay-ups also allowed benchrest shooters to make the sport’s rifle-weight limits while using heavier barrels and scopes, one reason pillar bedding now has a reputation for enhancing accuracy, even in hardwood stocks.

Another advantage of lay-ups was easier manufacturing than heat-molding. Anybody with a little know-how could construct a shell mold in the same way lay-up stocks were made, often by using a factory stock as a form. I’ve known several people who got their start making lay-ups this way in their garage shop, including Melvin Forbes of New Ultra Light Arms, who was successful enough that he soon wore out that mold, and spent somewhat more money to make an aluminum-based model.

Major factories started offering centerfire rifles with synthetic stocks. Weatherby may have been the first, with its Mark V Fibermark and Vanguard Fiberguard models. Both appeared in the catalog section of the Gun Digest annual in 1986, but others soon followed.

This trend drew more traditionalists like my father out of the, uh, woodwork, partly because some traditional stockmakers saw synthetic stocks as a threat to their livelihood. Synthetic stocks definitely cut into the use of wood stocks, but the effect (if any) on the custom fancy-walnut market was relatively small, because most customers already hated “plastic” stocks.

Still, a minor social eruption occurred when Dave Petzal, rifle columnist for Field & Stream magazine, wrote an article for the 1989 Gun Digest titled “I Sold All My Lovely Wood.” Petzal was (and still is) an extreme rifle loony, and for years had been paying top stockmakers to carve fancy walnut handles for his hunting rifles. The article provided examples of how several of his wood stocks went “bat-crazy,” often while out hunting, requiring rebedding.

Like many other traditionalists, Petzal initially disliked synthetic-stocked hunting rifles. He bought his first out of journalistic curiosity in 1979, a custom Remington 700 in .270 Winchester built by Chet Brown – but refused to hunt with it for several years because it was “too ugly.” When he finally did take the .270 afield, it performed so reliably “some” of his lovely walnut-stocked rifles became expendable. (“I Sold All My Lovely Wood” was a great title – but not exactly true. Petzal always kept some nice walnut-stocked rifles in his collection.)

Several stockmakers accused Petzal of being a “traitor.” This was amusing, because even back then synthetic stocks were well- established. The catalog section in the same 1989 Gun Digest listed seven rifle manufacturers, from Browning to Winchester, offering centerfires with synthetic stocks. Among major American rifle brands, Ruger was apparently the lone walnut-only holdout.

Nowadays you can walk into any store selling new firearms, and many, if not most, rifles will have synthetic stocks because synthetics primarily replaced figure-free wood on less expensive rifles, rather than putting custom stockmakers on welfare. In fact, many stockmakers who went ballistic on Petzal are still making lovely wood stocks.

Because synthetic stocks were so practical and affordable, their technology continued to evolve. Some lay-up makers, including Forbes, used more advanced fibers such as carbon and Kevlar, and aftermarket injection-molded stocks started appearing. The first I used were Butler Creeks, developed in the 1980s by Bill Heckerman of Belgrade, Montana, which also happened to be the home of the late Dave Gentry, a custom gunsmith who had been constructing his own lay-ups for several years. Gentry eventually made a pair of my early synthetic-stocked hunting rifles, a .280 Remington and .338 Winchester Magnum I hunted with extensively in the 1990s. (Gentry Custom LLC is still at the same Belgrade address, now ably run by Dave’s son Dennis.)

Dave Gentry also specialized in 98 Mauser rifles, including making complete actions – even a left-handed model, because he was a lefty. These obviously were expensive, but Gentry also produced a line of less expensive rifles for a while, based on the then widely available, inexpensive Mark X Mauser actions and Butler Creek stocks.

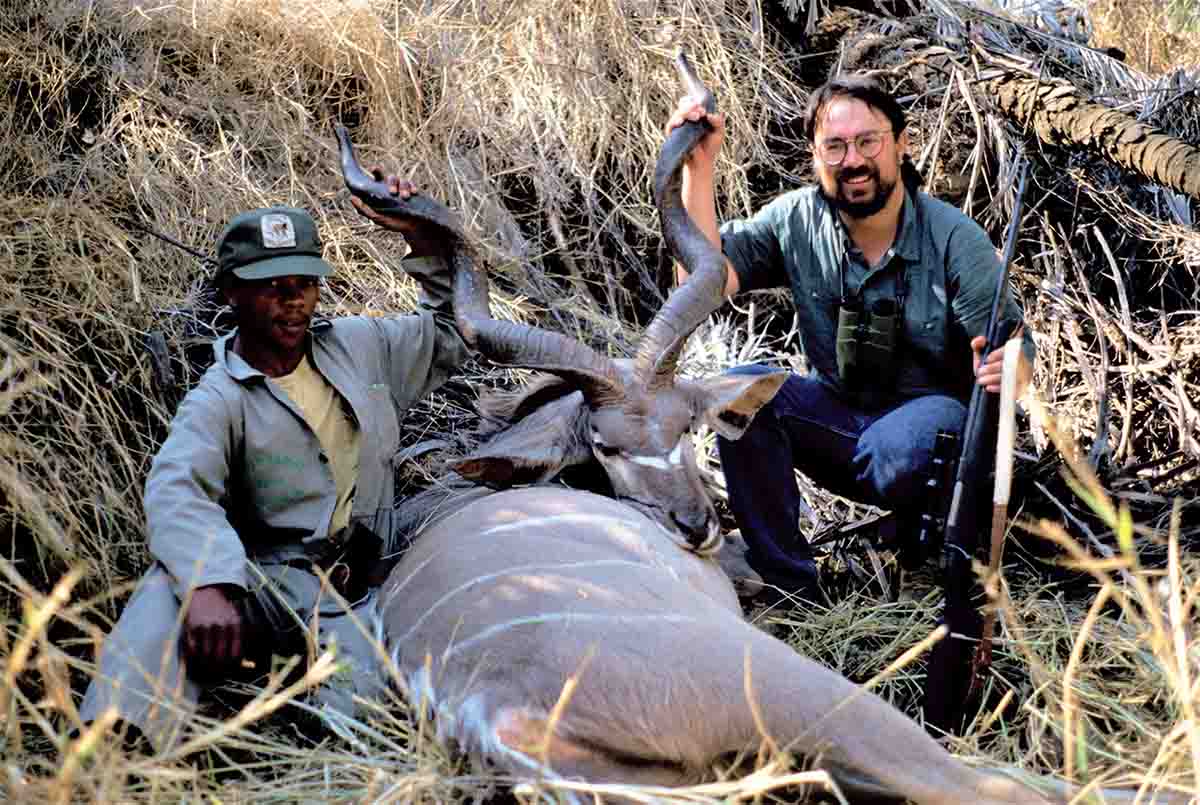

Gentry eventually introduced me to Bill Heckerman, and I not only tried a couple of his stocks but still have one as the “tough conditions” alternative for my Mark X Whitworth .375 H&H – also partially customized by Dave Gentry – which went on my first safari. Heckerman said the tooling cost around $200,000, but the stocks could then be produced for around $7 apiece because they were mostly made of recycled plastic – the reason some shooters call them “milk-bottle” stocks. (Essentially, lay-ups require far less tooling and initial investment, but they take more time to produce, while injection molding requires considerable investment but can produce far more stocks at less cost per unit.

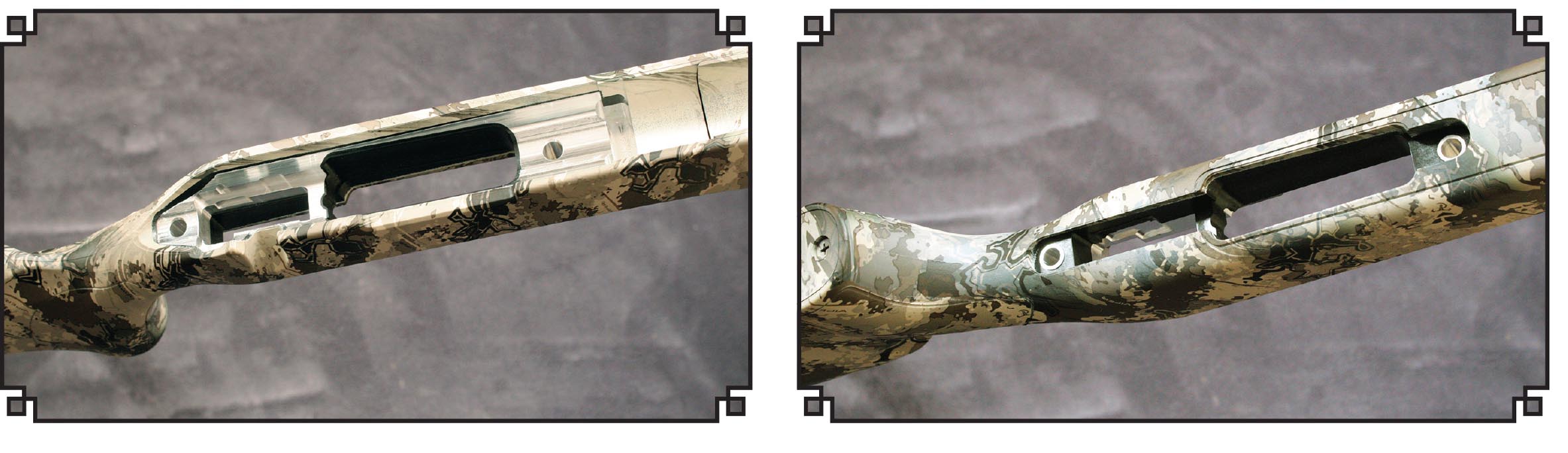

Butler Creek stocks were pretty flexible. This tended to reduce felt recoil slightly, but made consistent bedding more difficult – a problem that has affected “affordable” injection-molded stocks ever since. This problem can be solved both by physical design, these days usually involving cross-reinforcement walls inside the forend, and by including stiffening materials in the thermoplastic itself, along with metal “bedding blocks” inside the stock’s action area.

A good example is the AccuBlock Long Range Composite (LRC) stock made by Stocky’s (newriflestocks.com), a major manufacturer and retailer of not only stocks but other gun parts.

Stocky’s owner, Don Bitz, sent me four samples of the LRC to test, all for Remington 700 actions.

These turned out to be noticeably heavier than many other injection-molded stocks, a trend becoming far more common as centerfire rifles continue to evolve in the twenty first-century, due to a couple of factors.

First, competition rifle shooting has been rapidly increasing in the U.S., particularly long-range shooting, and heavier rifles are easier to shoot accurately. The increased demand for accuracy not only resulted in more weight but stocks designed specifically for prone shooting, along with at least some adjustability, or replaceable parts such as buttstock combs, forends and pistol grips. Also, bedding blocks such as the aluminum AccuBlock often enhance accuracy.

Second, hunting is declining in the U.S., and at the same time many people hunt differently than we used to. Instead of hiking over hill and dale, more of us sit in stands overlooking planted fields (a technique particularly popular east of the Rocky Mountains) or, in wilder country, on ridges overlooking likely country. This style of hunting is easier than hiking miles in steep country, the original reason for lighter mountain rifles – and the number of older hunters has increased considerably over the past few decades. In 1991, 28 percent of hunters were 25 to 34 years old, the highest percentage of any age group, with 23 percent aged 45 to 64. By 2017, this became the largest age group – doubling to 46 percent.

In general, typical factory walnut stocks and their injection-molded equivalents weigh around 2 pounds. The Stocky’s stocks ranged in weight from 2 pounds, 14 ounces (classic-styled sporter) to 3 pounds, 15 ounces for the vertical pistol-grip and thumbhole models. This extra weight is partly due to the AccuBlock, but also due to the stiffer stock material, combining fiberglass with nylon.

The molds for inexpensive injection-molded stocks are comparatively simple, but Bitz said the “machine for the LRCs is about two-thirds the size of a school bus,” with interchangeable parts to create the different designs. The machine is also cooled before a freshly-molded stock is removed, by pumping water through its parts. This prevents the stock from warping, a common occurrence when warm stocks are released from the confines of the tooling. The AccuBlock is also molded right into the stock instead of being attached later, and it is designed so the receiver partially “floats,” so the front and rear of the action do not contact the synthetic shell.

Along with being painted in various color patterns, this is why LRCs cost somewhat more than many other drop-in injection- molded stocks, some of which still retail for under $100. However, the standard price for finished LRC stocks is $299.99, around half the price of finished lay-up stocks from several companies – including Stocky’s, which as this was written was producing a new lay-up stock with a composite (not aluminum) AccuBlock.

I eventually chose to keep the “classically” styled LRC stock, the M50, which has a replaceable cheekpiece to accommodate different scope-heights, and dropped in the barreled action of one of my favorite varmint rifles, a Remington 700 .204 Ruger. This rifle had already been through some changes since acquiring it as a brand new VTR (Varmint Target Rifle) with a triangular contour barrel and relatively flexible injection-molded stock with a wide, ventilated forend to help air-cool the barrel.

It shot well, but despite the ventilation I still fried the barrel relatively quickly on prairie dog towns, so acquired a new “take-off” stainless sporter barrel from a custom gunsmith. This did not look right inside the VTR stock, so I bought a walnut CDL 700 stock. After bedding the barreled action with Brownells Acra-Glas Gel, the rifle shot very well both with Hornady V-MAXs and Berger hollowpoints.

However, after dropping the barreled action into the M50 stock, the .204 shot even better, with average five-shot groups shrinking around 25 percent. This was without using epoxy to skim-bed the AccuBlock, as some shooters often do even with a bedding block. Don Bitz said this is pretty normal with the aluminum AccuBlock stocks, a claim I intend to test some more with a composite AccuBlock stock. The extra pound of stock weight, along with the straight comb, also allowed me to see bullet holes appear in the target – also handy when shooting at prairie dogs.

Stocky’s also sells a wide variety of stocks other than its own models, including laminates and even walnut and several brands of synthetics. While quite a few older shooters still grump and grumble over “plastic” stocks, such synthetics offer a wide variety of alternatives to less inflexible shooters. I still own several rifles with lovely wood, and others with not-so-lovely wood, including some classic factory rifles. I do not intend to replace their walnut, but also do not consider myself a traitor for often hunting with twenty-first- century rifles featuring lighter or heavier synthetic stocks.