Walnut Hill

Fore-Armed to Excess

column By: Terry Wieland | July, 20

About 15 years ago, there occurred one of the less pleasant memories of my pursuit of the perfect rifle. For many years, I’d entertained a lurking desire for a .250-3000 built on a Mauser Kurz action, if I could find one I could afford. That never came to pass, but instead, Dakota Arms began offering a short version of its 76 action, an enticing cross between the Mauser 98 and the pre-’64 Model 70.

The cost of having Dakota build a rifle was less than I would have expected to pay for just the short Mauser action, even had I found one, so the choice was obvious. At the custom gunmakers’ show that year, I laid out $1,000 for a beautiful walnut blank, sent it to Dakota out in Sturgis South Dakota, and began counting the days.

The order sheet stated clearly that I wanted a “slim, trim deer rifle.” On the appointed date, I arrived in Sturgis, was presented with my prize, opened the box and found . . . absolutely not what I wanted. Although the basic specs were fine, the forend widened out ahead of the action into a broad, flat beavertail on which my long- anticipated fleur-de-lis checkering was grotesque. Instead of graceful and flowing, it was misshapen in order to accommodate that oversized, ugly forend.

When the stockmaker was asked for an explanation, he replied that, since it was a .250-3000, he assumed it would do double duty as a varmint rifle, so he put a varmint stock on it. What about my written instructions for a slim, trim deer rifle? “Well,” he muttered, “I thought this would work for both.” I told Dakota to keep the rifle and swallowed the loss.

It was that moment that really awakened me to the vagaries of forends, and made me aware of just how important they are, not just to the aesthetics of a rifle but also to its handling qualities. Especially with a rifle intended to be carried a lot, they can make all the difference.

Rifles made before 1930 are almost always very slim, even those that were made for target shooting. After 1930, however, as hot .22 centerfires proliferated and riflemen became woodchuck hunters, there sprouted a fashion for making forends that were more suited to shooting from a bench, resting the forend on a sandbag. I have never grasped exactly how such a forend helped a hunter in a field of clover shooting prone at a woodchuck in the dim distance, but they took over all the same. James J. Grant, writing about single-shot rifles in the 1950s, noted that most of the single-shot actions that had been reworked into hot varmint rifles had thick, wide forends. Their owners “felt that life could not be complete” without a “target” forend on their rifle.

As with most fads in shooting, manufacturers then proceeded to go right off the deep end. Any rifle that might conceivably be used – somewhere, sometime – to shoot from any sort of a rest, was given a forend resembling a dock pylon.

About two years ago, I more or less accidentally acquired a nice Stevens 44½ Schützen rifle from the early 1900s. Although a target rifle, it was fitted with a graceful schnabel forend typical of the time. It reawakened my interest in fine single shots, and especially Stevens rifles. When a later Stevens Model 417 appeared in an auction, I was immediately interested. The rifle, made in the 1930s, was in almost new condition and obviously worth a close look. When I picked it up, however, I lost interest immediately. True to the style of the ’30s, it had a bulbous forend that was all out of proportion to the action. The buttstock, presumably made to match, had a high, straight, thick comb and a steep pistol grip like a match rifle. As for the handling, forget it. It was like picking up a length of four-by-four.

The Stevens 417 is a .22 Long Rifle, not even a Hornet, much less a Zipper or something comparable. There is no earthly reason to fit it with such a stock, except as a marketing ploy to suit the fashion of the time.

A year or so after that, I acquired a Marlin Model 39 made in the 1920s, which was almost identical in overall shape to its parent models, the 1891 and 1897. These were made in the style of early lever actions, like the Winchester 92, intended to slip into a saddle scabbard. I was instantly enamored, partly because of the smooth action and flawless operation, but also because it just felt good in the hands. As a friend of mine puts it, it was ideal for “woods walking.” It carries comfortably in one hand for hours at a time and comes to the shoulder in an instant. The forend is the same width and depth as the front of the action and stays slim as it stretches down the barrel. There is plenty of wood to grasp, but not so much that it gets in the way or spoils the rifle’s slim lines.

In a reprise of the Stevens episode, I began searching around for a newer 39 – one that would gladly accept high-velocity ammunition, which the older one will not. One came up for auction, was made in the early 1960s and looked almost new. How could I resist? But, echoing the Stevens episode to the smallest detail, when I picked it up, I immediately lost interest. From the photographs, I knew the forend was oversized but underestimated just how much it would degrade the handling. Instead of being a “woods walker,” this 39 was made to be a bench rifle. I decided I could happily live just shooting standard-velocity .22s in the older one.

I wish I could say the fashion for bulbous forends passed into history and we were back to stocks that look and feel good. Alas, that is not the case. Very few rifles today come from the factory with a stock that does not feel fat (for lack of a better word) in the hands. Pistol grips are almost always too thick, and forends are either big and round or flat and wide, even on composite stocks, where there is no issue of strength to contend with.

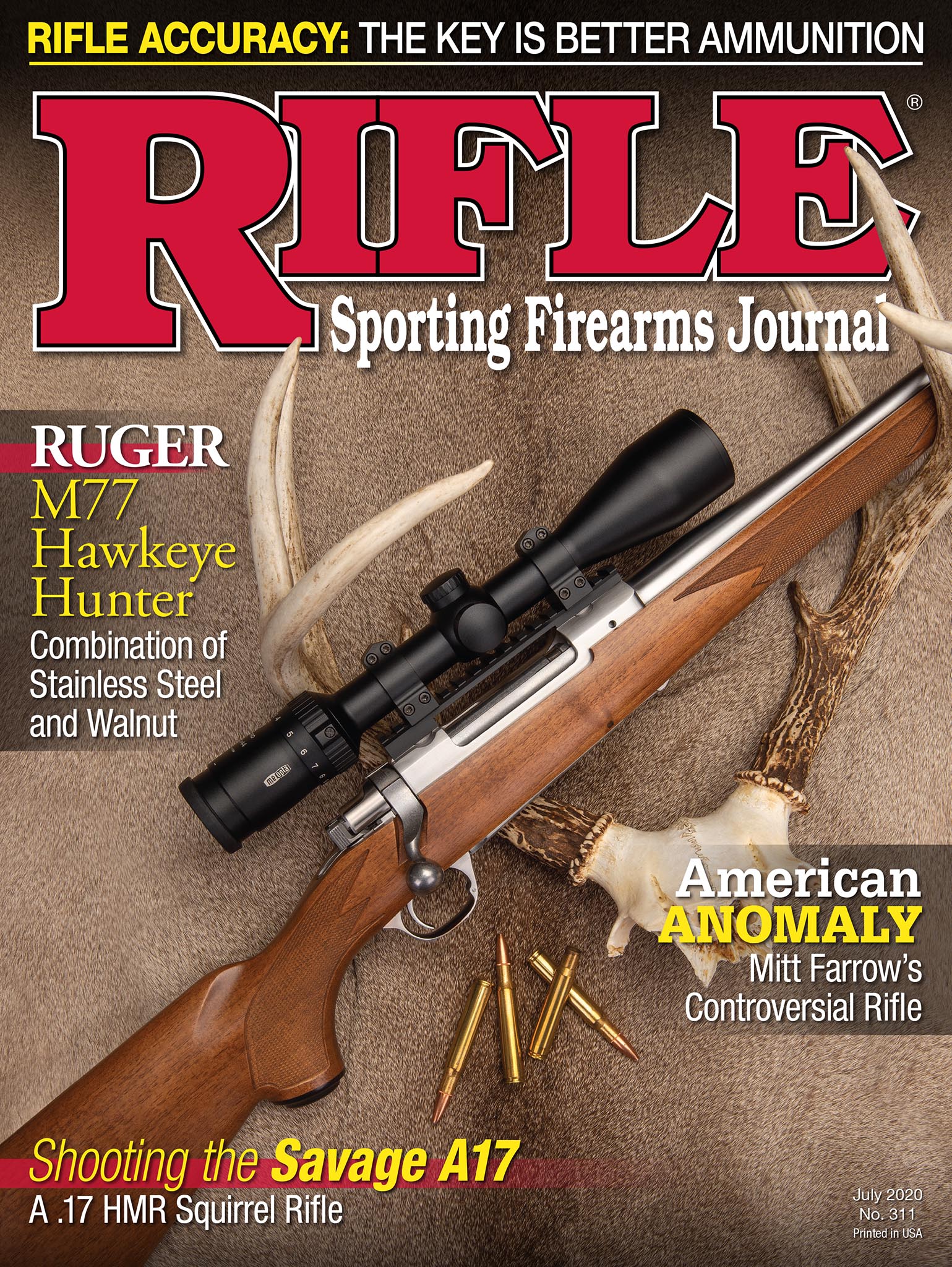

The last factory rifle I handled that really felt good was a Winchester Model 70 Featherweight, which had a nice piece of walnut and a reasonable facsimile of the original schnabel forend that adorned it back in the 1950s. And, in all fairness, I should mention that most of the Ruger bolt actions with composite stocks – I’m thinking here of the 77/44, 77/357 and Hawkeye FTW Hunter – all have stocks not far removed from the original one designed by Lenard Brownell for the Model 77 in 1966. That stock was one of the best ever to grace a factory rifle. But those, alas, are exceptions.

If someone backed me into a corner and demanded an explanation for why this has come to pass, my best guess would be that very few hunters do much walking anymore. If they did, they’d want a rifle that carried easily and comfortably in the hand, and would demand that manufacturers provide them.

Thinking back to the episode in Sturgis with the disappointing .250-3000, I remember that the stockmaker looked at me like I was nuts, and a Dakota dealer from New Jersey immediately said, “If he doesn’t want it, I’ll take it!” Where it ended up from there, I have no idea. Knowing how the world works, though, I expect by now it’s been rechambered to some “improved” version, fitted with a bipod and 18x scope and gets taken out once a year to puncture paper targets on a shooting range.