Walnut Hill

Belted Iconoclast

column By: Terry Wieland | March, 23

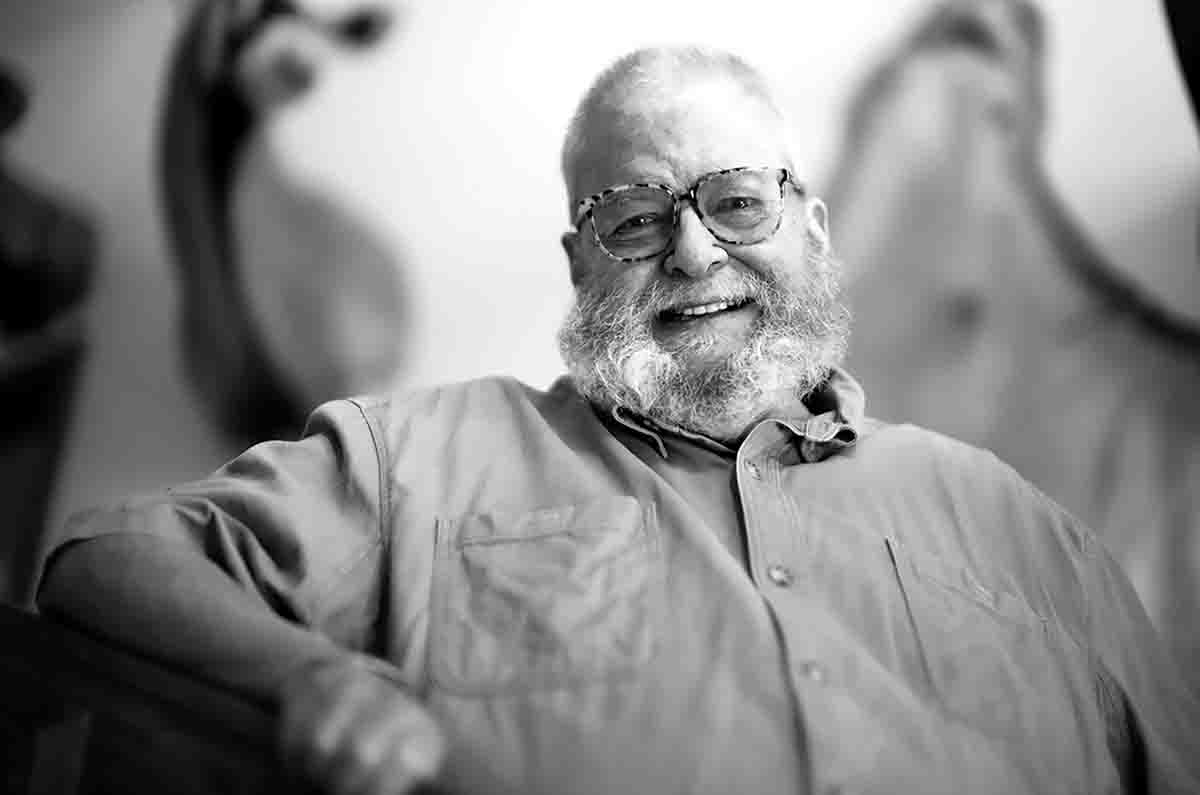

On first meeting, Tom did not give the impression of being a highly erudite man of letters. In fact, he resembled nothing quite so much as a bear whose slumber has been disturbed. When I met him the first time, around 1990 at a publisher’s gathering of some description, he looked like a burly and unkempt lumberjack – or would have, but for the ever-present martini in a glass the size of a birdbath.

Of course, I had known of Tom for many years before that meeting, having admired his stuff in Sports Afield through the 1980s. When I went to Alaska to hunt brown bears in Prince William Sound in 1988, my outfitter, the equally burly Gary Pahl, showed me some photographs of Tom, taken when he’d hunted with Gary a few years before.

Tom was holding the head of a fine Dall ram in one hand and his rifle in the other. It was a Weatherby Mark V in, as I later learned, .270 Weatherby Magnum.

This was surprising, in a way. At the time, Weatherby rifles and cartridges were held in general disdain by mainstream gun writers. It was the result of inverted snobbery, based on the fact that Weatherby was located near Hollywood, and that Roy Weatherby trumpeted the fact that actors and politicians used his rifles – many of them gold-plated, with outlandish stock inlays. Such people, it was felt, knew nothing about rifles, whereas we do, and we don’t use Weatherbys.

Regardless of who used them, however, Weatherbys were fine rifles; the Mark V action is excellent, with one or two failings, and almost all of the Weatherby cartridges are superb.

The other factor working against Weatherby at the time was a growing dislike of belted cartridges, and of course, Weatherby’s cartridges were all belted.

The knock against belts was the belief they can’t be as accurate as a rimless bottleneck with near-parallel walls, such as the .280 Remington Ackley Improved (a darling in 1988), which headspace on the shoulder. The anti-belt crowd became so manic that one writer even opined, in print, that belted cartridges were “noisy” sliding out of the magazine into the chamber. This, it was alleged, would alert that wounded buff over there in the bushes and you’d be dead meat as a result.

If there is even the faintest modicum of truth to that claim, neither my ear, nor a recording device used by professional radio technicians, could detect it. I know Cape buffalo are credited with extraordinary hearing, but even so.

Tom McIntyre’s admiration for Weatherby rifles and cartridges came about originally because he lived in Downey, California, a Los Angeles suburb a little way along Firestone Boulevard from the Weatherby operation in South Gate. Tom spent a lot of time in the store, which combined rifle-making facilities with a vast (for the time) retail operation. The walls were covered with heads and horns, including an elephant shoulder mount with tusks and trunk extending out from the wall, seemingly, forever.

In the past, I’ve been critical of Roy Weatherby for some of his bizarre claims about the effect of high-velocity bullets on big-game animals. Contrary to a piece he wrote in Gun Digest after a long African safari in the early 1950s, a Cape buffalo does not collapse in a smoking ruin after being hit “in the ham or in the hoof” by a bullet from the sizzling .257 Weatherby. Sorry, but no.

But I digress. As Tom told me years later, he grew up admiring Weatherbys, and when he started hunting with them, soon proved just how effective they could be, given the requirement of putting the right bullet in the right place, to utilize the effect of all that velocity.

When Tom and I were growing up (a continent apart, and he was three years younger) the reigning rifle gurus were Jack O’Connor in Outdoor Life and Warren Page in Field & Stream. O’Connor favored the .270 Winchester and .30-06, while Page hunted around the world with a 7mm Mashburn, a belted wildcat that predated the 7mm Remington. Both were early recipients of the Weatherby Trophy for big-game hunting, but it did not influence either when it came to choosing cartridges.

The only prominent writer/hunter of that era who used a Weatherby was Elgin Gates, also a Californian, and also later a Weatherby Trophy winner. Gates allegedly shot everything, up to and including elephant, with a .300 Weatherby. I say allegedly because it is difficult to know, 60 years later, how much of what he wrote was true and how much was the product of his overwhelming competitiveness that stopped at nothing to be number one.

As I recall, Gates had most of his articles published in Gun World – at least, that’s where I read him – and I was an early admirer. Such is the credulity of youth.

In 1975, I bought my first serious big-game rifle, a .300 Weatherby Mark V, and used it on several expeditions in the late 1980s for caribou in Quebec, brown bear in Prince William Sound and moose in British Columbia. To this day, I believe the .300 Weatherby is the best and most useful of all the big .300s, but only provided the rifle has a barrel at least 26 inches long. From a 24-inch barrel, it is a barking, slamming loudmouth of a cartridge whose velocity falls several hundred feet per second short.

In 1990, I acquired one of the finest rifles I’ve ever owned. a Safari-grade custom .257 Weatherby Mark V. Out of the box, with factory ammunition, I shot a five-shot group that measured .60 inches. Loaded with then-new 115-grain Trophy Bonded Bear Claws, I took that rifle

to Africa. Just as Tom McIntyre had experienced a few years before, there were some raised eyebrows, since “those who knew” did not use Weatherbys. However, the rifle acquitted itself well, and the eyebrows were lowered.

I don’t know how long Tom used a Weatherby. We never discussed it, and he was always more of a hunting writer than a gun writer. John Barsness, who knew Tom well and guided him on a trip in Montana in the 1980s, said he used a .300 Weatherby.

My experience with Weatherbys included the .416 Weatherby in 1990, an excellent cartridge, and later, a custom .270 Weatherby. The former did for two Cape buffalo – my only one-shot kill and a six-shot kill. The .270 took a bull elk in Montana in 2012.

Gradually, my infatuation with Weatherbys wore off, mainly because of the lack of a three-position safety on the Mark V action. I never fell out of love with, or became disillusioned with the cartridges, however. The .257 was and is superb – in a class by itself in the world of .25s.

One last comment on the accuracy of belted cartridges. When Kenny Jarrett set out to design the ultimate big-game cartridge, he based his .300 Jarrett on a belted case. Kenny knows more about accuracy in both rifles and cartridges than anyone else I know. His .300 Jarrett is essentially the .300 Weatherby but without the sexy double-radius shoulder. If Kenny thought there was anything the slightest bit wrong with a belt, he wouldn’t have used one.

Jack O’Connor was a rifle nut “of the most depraved sort,” while Warren Page’s interest centered on benchrest shooting. Tom McIntyre, however, was a hunter. He loved rifles and shotguns, to be sure, but hunting was his passion. His .270 Weatherby did everything he wanted it to do and he didn’t really question it. Also, Tom didn’t much care what others thought, and he certainly never went out of his way to fit in.

Possibly, his connection with Weatherby gave him a private snicker at annoying the crowd. I wouldn’t put it past him.

Tom McIntyre’s last book, Thunder Without Rain, about African buffalo, is scheduled for publication in February 2023.