Down Range

Japanese WWII Sniper Rifles

column By: Mike Venturino | March, 18

A good example is Japan’s World War II sniper rifles, of which it fielded two basic models, the Type 97s and Type 99s. Production of the former outnumbered the latter by a considerable margin, but manufacturing figures for Japanese rifles are spotty. I was able to find a Type 97 in 2006, but it took until 2014 to find a Type 99.

Terms for Japanese weapons can be confusing. For example, both standard infantry rifles and sniper rifle versions adopted in 1939 are named Type 99. The only differences between them are a bent bolt handle and left rear receiver rails that are drilled and tapped for a quickly detachable scope mount. However, Type 97 sniper rifles adopted in 1937 bear the same relationship to Type 38 rifles, which had been Japan’s infantry standard starting in 1905. The only difference here is the bolt handle and quickly detachable mounting system.

Types 38 and 97 are chambered for the semi-rimmed 6.5x50mm cartridge with a 139-grain bullet rated at 2,500 fps from 31.5-inch barrels. Experience gained when fighting on the Asian mainland convinced the Japanese that they needed a cartridge with long-range potential. The Type 99 was developed for a brand-new rimless 7.7x58mm. Its bullet was 179 grains with a velocity about the same as the 6.5mm, but from 25-inch barrels.

Japanese rifles certainly are not much to look at. Buttstocks are spliced together laterally as a frugality measure due to Japan’s dearth of wood. However, metal polishing and blueing on prewar and early war samples are well done, as is the quality of machine work. Type 99s were even given chromed bores throughout most of production, which accounts for so many remaining very shootable despite the miserable conditions in which they were used.

Some exterior features look odd to American riflemen. Instead of bolt knobs being a rounded ball, they are oblong. Type 99s and some Type 97s have a peep sight placed on the barrel where normal open sights are found on other nations’ military rifles. Type 99 rear sights have folding wings that are meant for determining “lead” when firing at low-flying aircraft. Safeties on both versions are rounded, knurled knobs at the bolt’s rear. Beyond that, both types are simply knockoffs of Peter Paul Mauser’s ideas, including internal box magazines holding five rounds in a staggered column.

It is my opinion that the Japanese military considered Type 97s and 99s as infantry rifles first, and sniper rifles second. For instance, Japanese sniper rifles have a completely unobstructed view of their iron sights because the scope is mounted offset to the left. With their quickly detachable mounting system, Japanese doctrine was for the scope to be carried on the belt in a hard case and only attached when needed. Some German rifles had “tunnels” through the mounts so iron sights could still be used, but British, Soviet and American rifles did not. The Japanese system also allowed the Type 97 and Type 99 magazines to be fully charged by stripper clips. Most other countries’ sniper rifle magazines had to be loaded one round at a time.

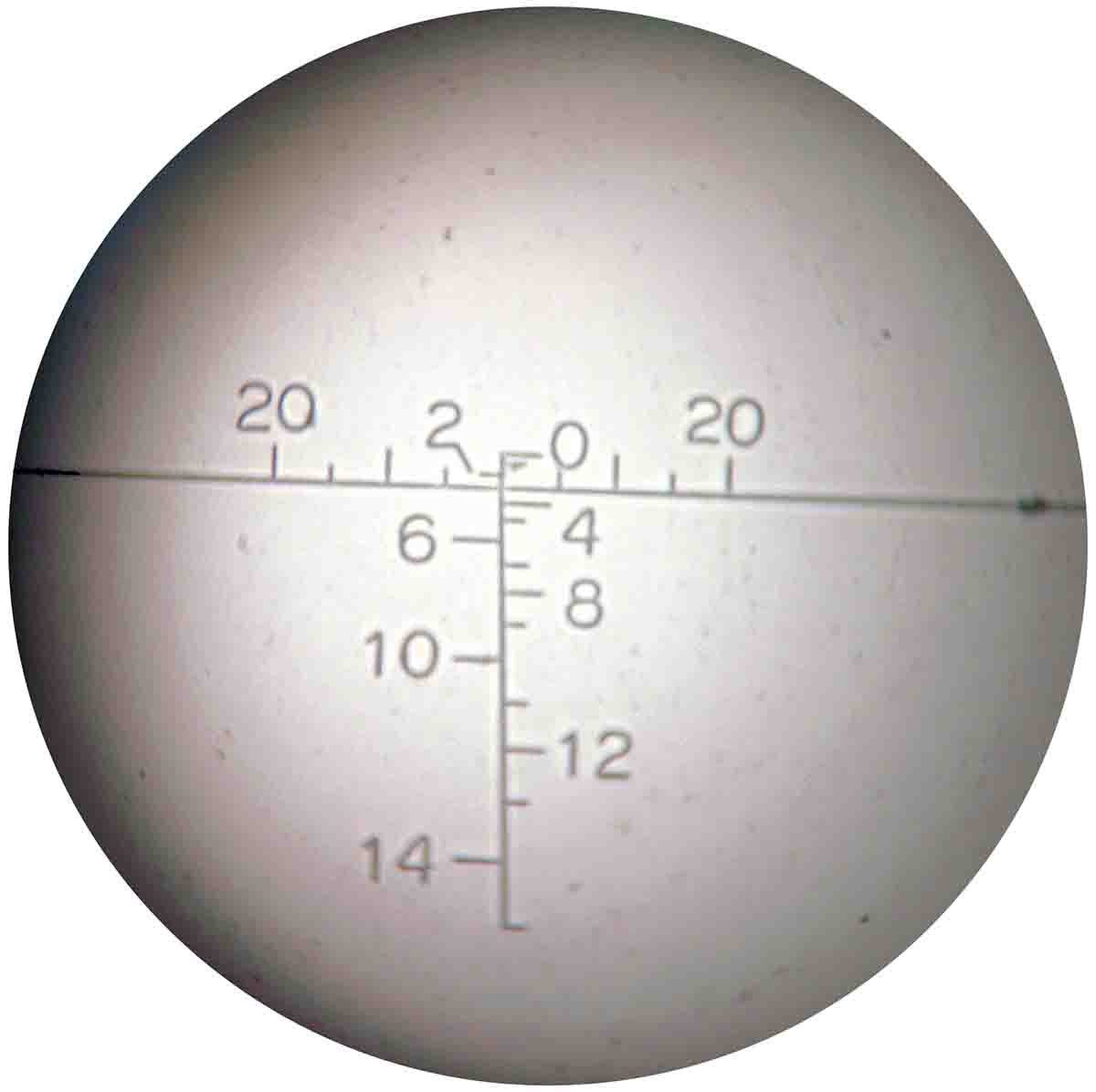

Then there is the matter of scope adjustments. There were none; neither in the scope or in the mounts. (A small number of Type 99s were given adjustable scopes late in the war.) Rifles and scopes were zeroed at arsenals before being issued. To compensate for lack of adjustments, reticles were very complex, with hash marks for hold-off in regard to elevation and windage. The soldier was expected to learn and memorize which marks were needed for various conditions. Most German scopes only featured elevation adjustment in the scope itself, but windage was changed by the rear mount. American, British and Soviet scopes were completely adjustable. (The 8x Unertl scopes used by the U.S. Marine Corps, of course, had fully adjustable mounts.)

Grouping ability is another reason I think these sniper rifles were considered basic infantry rifles by the Japanese. Neither of mine are what I would consider “tack drivers,” and research has turned up no mention that Japanese armorers picked especially accurate rifles for sniper conversions. My examples are about 3 to 4 minute- of-angle shooters.

To someone who grew up using American sporting scopes, trying to figure out the Japanese sniper scope system is a formula for headaches. One afternoon I spent three hours and about 80 6.5mm handloads trying to shim my Type 97’s mount so it would be zeroed at 100 yards. I got it done, too. Next time out that rifle’s zero was completely off again. So what I am determined to do is follow Japanese doctrine. My 2018 New Year’s resolution is that I’m going to find which hash marks get me on at 100, 200 and 300 yards, and write them down. Then at last maybe I will be able to reliably hit something with them.