Light Gunsmithing

Bolt Guns and Bedding Barrels

column By: Gil Sengel | March, 18

It was not long ago that the hot topic among riflefolk looking to improve accuracy and eliminate those unexplained, out-of-group shots known as “flyers” was how the barrel fit in the stock. Was there contact between the barrel and forend? If so, where and how much? Should there be contact? Many rifle owners and all gun writers had their opinions. Then when plastic stocks began to appear, the experts blamed wood for all the world’s problems, declaring that no serious shooter should henceforth own a riflestock made from a tree. Good heavens!

Today we don’t hear much about barrel bedding. This is partly due to modern AR-15-looking, bolt-action rifles having no contact at all between barrel and forearm. Thus there is no bedding surface, and they shoot very well, indeed.

Another factor is that several modern bolt guns come with accuracy guarantees, usually three shots in an inch or less at 100 yards. Even though purchasers never use the factory loads these rifles were tested with, the guarantee proves the company that put the rifles together knew what it was doing. Handloads are easily worked up to meet the accuracy claims. There is no need to fiddle with bedding.

This is all well and good, but it still leaves tens of millions of bolt rifles, many of which will benefit from barrel bedding efforts. But why? Is it really the wood stocks? Perhaps to some extent it is, but modern stock material (except some laid-up fiberglass) will warp and deform if left too long in the hot sun. Like wood, it will also deform and compress over time if guard screws are drawn up tightly. It is tempting to blame the stock, but after seeing a great number of rifles that have been restocked in both plastic and laid-up fiberglass and then did not shoot one bit better than in their wood stocks, I believe the problem lies elsewhere. It is not the barrel or barreled action fit to stock, but barrel fit to receiver. Here is where barrel fit to stock can have a major effect.

After nearly 50 years of being in shops where fitting rifle barrels was done, as well as talking to gunsmiths and trade school graduates who learned the process from others, it seems almost everyone has a different take on the subject. For example, one shop did a couple rebarrel jobs a month, mostly building lightweight hunting rifles. Some customers specified the rebarreling part be sent out to well-known barrelmakers who also fit and chambered their product. Those completed in-house were the product of a fellow who used a length of galvanized pipe to extend the handle of his action wrench. Barrel threads were cut “tight,” as he termed it, then the receiver was screwed on using brute force.

Over the years it was discovered that many gunsmiths installed barrels this way. When the rifles were completed, the ones with the barrelmaker-installed tubes never had any accuracy complaints – not so with the in-house jobs. The shop owner told customers that light barrels and old military actions often just turned out that way. Garbage! Barrelmakers go to great pains to stress relieve their barrel steel. One can only imagine the stress put into a barreled action when the barrel is installed with such force.

The opposite condition is also common: Many barrels have been removed (especially factory-installed barrels) that seemed tight, but when backed out even the smallest amount they became sloppy-loose. When such a barrel heats up a bit, or is taken out in freezing weather, it’s easy to imagine it moving a tiny amount in the threads. Of course, the scope is firmly attached to the receiver and isn’t going to move. Goodbye accuracy and consistent point of impact.

Knowing this, it’s easier to see why barrel bedding can make a difference. The only solution for bolt-action rifles (aside from properly installing a new barrel) is to restrain the barreled action in the stock as much as possible. However, this is only after determining that accuracy, flyer and point of impact problems exist with the barrel free floating, and scope, bases, rings and mountings are free of defects – especially the scope. I often have replaced a customer’s scope with an old Weaver kept in the shop for just this purpose and more than once found that problems disappeared.

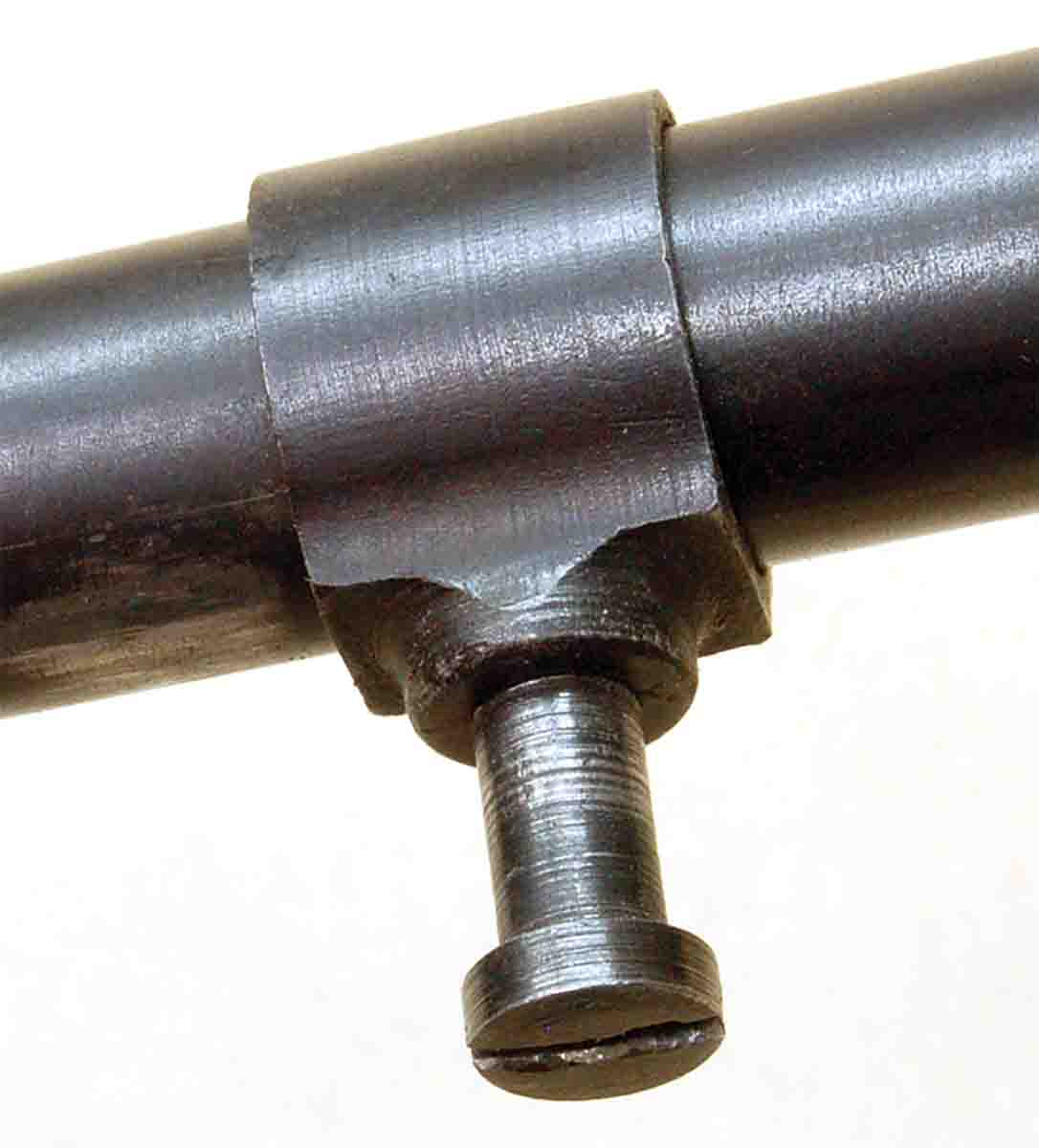

At any rate, the receiver must be set firmly in the stock, both at the bottom and sides plus the cylindrical portion of the barrel forward of the receiver ring. Epoxy bedding is the only way to do this. Adding bedding pillars is also a very good idea. This was covered in Rifle No. 255 (March/April 2011). Don’t forget to lightly scrape the sides, front and bottom – definitely the bottom – of the recoil lug recess so the barreled action slides into the stock and bottoms-out on the bedding using only firm hand pressure. Then shoot the rifle again, with the barrel free floating, to see if accuracy has improved or that flyers have been eliminated. If not, proceed to the next step.

It is important, however, to be certain any screws pulling the barrel into the stock with a block attached to the barrel or a narrow barrel band are still free to do their job. After the epoxy cures, draw these up firmly but not nearly as firmly as guard screws. The narrow barrel band is often seen on European sporters and even U.S. custom rifles made between the wars. It can have a very positive effect. Unfortunately, they are no longer available as an installable part and must be made up in the shop if wanted.

Full-length bedding with or without the barrel pulled down firmly in the forend was once common but has been forgotten today. Yet it is still useful in some instances, which brings up a final thought.

Many Americans insist on using the lightest trick bullet they can find pushed to the highest velocity possible. This is okay for modern guns. Old classic, thin-barreled hunting rifles are another matter. Ordinary cup-and-core bullets of the weights originally intended for the rounds in question, pushed at near-original velocities, are the answer. Don’t try to make a 7x57mm into a “7mm Vertically Challenged Super Ultra Magnum.” If we are going to shoot these old rifles, we generally need to play by their rules.