Short and Sweet

Ruger 77 Series Carbines Are Too Good to Miss

feature By: Terry Wieland | March, 18

Other members of this particular club include the patriarch Mauser ’98, the Winchester Model 70, Remington 700 and the Savage 110. All have had adventurous and varied lives, and to claim some sort of exclusive status for the Ruger 77 in the face of all the variations and iterations of the others would be highly presumptuous. However, it’s fair to say that when it comes to variety, the Ruger 77 certainly belongs in the same crowd.

As the Mauser ’98 has proven over and over, if you start with a basically sound and simple design – refined to the point of genius – it becomes eminently adaptable. In Ruger’s case, however, the 77 has trodden some ground where even the ’98 has left no footprints.

It’s impossible at this late date to determine exactly who, in which product meeting, suggested adapting the bolt-action Model 77 to the .44 Magnum. On the surface, the idea seems absurd. Putting a short cartridge in a long action is inefficient, for one thing, and the .44 has a rim, for another. Since all .44 bullets are either flatnosed or round and blunt, the feeding problems can only be imagined. One parallel to this idea, dating back many years, was when Winchester chambered the Model 70 for the tiny, rimmed .22 Hornet. At the risk of being lynched, let me say that always seemed idiotic to me. In that same imagined meeting at Ruger, someone may have jokingly suggested that if Ruger was going to chamber the 77 for the .44 Magnum, why not the .22 Hornet as well? After all, those ancient Model 70s are serious collectors’ items now. And if we’re going to do that, why not toss in the .357 Magnum?

At this point, my imagined meeting dissolves into laughter, yet jumping ahead a few months, what do we find? A completely scaled down, redesigned Ruger Model 77 chambered for exactly those three cartridges – three of the neatest little carbines to come down the pike in a good long while, suitable in one configuration or another for everything from woodchucks in the garden to raccoons in the corn to deer under the old apple tree. Someone in authority at Ruger obviously took those suggestions seriously and ran with them. The result was the Ruger 77/44, 77/357 and 77/22.

It seems that Sturm, Ruger & Company’s corporate motto could well have been “Nothing is impossible.” The company single-handedly resurrected the single-action revolver and the single-shot rifle (the Blackhawk and No. 1, respectively) as well as bringing the .416 Rigby cartridge back from the dead in 1993 with its magnum Model 77. These were decisions made by gun enthusiasts, not bean counters, and every one of them paid off magnificently.

Some of Ruger’s daring moves have been deemed failures. The semiautomatic .44 Carbine from long ago is among them, but since it lasted in the lineup for 25 years, that judgment is highly debatable. At the speed with which new rifles come and go these days, a quarter century of production looks highly respectable. I bought one of the carbines in 1985, the year it was discontinued, and hunted deer with it for a couple of years. I parted with it before it became a desirable collector’s item (story of my life) but retained a taste for the .44 Magnum in almost every configuration.

Ruger’s designers approached the problem of adapting the hefty Model 77 bolt rifle to the squat .44 Magnum by completely reworking the action. It is not merely shorter, in the sense that the Mauser ‘K’ (kurz) action was shorter; it has been extensively reconfigured to accommodate the short cartridges.

The bridge has been lengthened to twice normal dimensions (2.4 inches versus one inch on the Model 77 Hawkeye) and it has two rear dovetails for scope mounting instead of one. In addition to accommodating different-length scopes, if that’s required, this also allows fitting an after-market receiver sight at the right distance from the eye.

The bolt lugs have been moved from the head of the bolt to a position just forward of the bridge. One turns into the floor of the action while the other is braced by the top of the bridge itself.

The two-piece bolt’s forward half remains stationary while the rear half with the lugs rotates into position.

The 77’s standard Mauser-style extractor has been eliminated and replaced by a smaller, spring-loaded claw that handles rimmed cases with ease. One of the advantages of the Mauser-type extractor is that it controls feeding of the cartridge from the magazine into the chamber by gripping the rim as soon as the bolt begins to push it forward. In the short Ruger, however, this is not necessary because Ruger discarded the traditional, staggered box magazine and replaced it with a rotary spindle (or spool) magazine.

Historically, the two rifles that are most associated with the rotary magazine are the Mannlicher-Schönauer and the Savage 99. Both companies began using a rotary design before 1900. In the Savage, the magazine is completely contained within the steel receiver; the Mannlicher’s can be easily removed for cleaning, but it does not hold cartridges while this is done.

Ruger went one better and combined the rotary action with a box that can be removed, complete with cartridges. It can be left in the rifle and loaded like a Mauser box or removed and loaded like a clip.

One major criticism of all rotary magazines is that they fit one cartridge exactly, so the rifle cannot be rebarreled or rechambered to a different one. This is quite true in the case of, say, the Mannlicher Model 1903. Various gunsmiths have undertaken the job, and all that I know of swore never to do it again. However, rotary magazines have an even more important virtue: They provide unfailingly reliable feeding and are very quiet in the process. Since the spindle cradles each cartridge snugly, it cannot slam back and forth under recoil, damaging the spitzer tip or jarring the bullet loose.

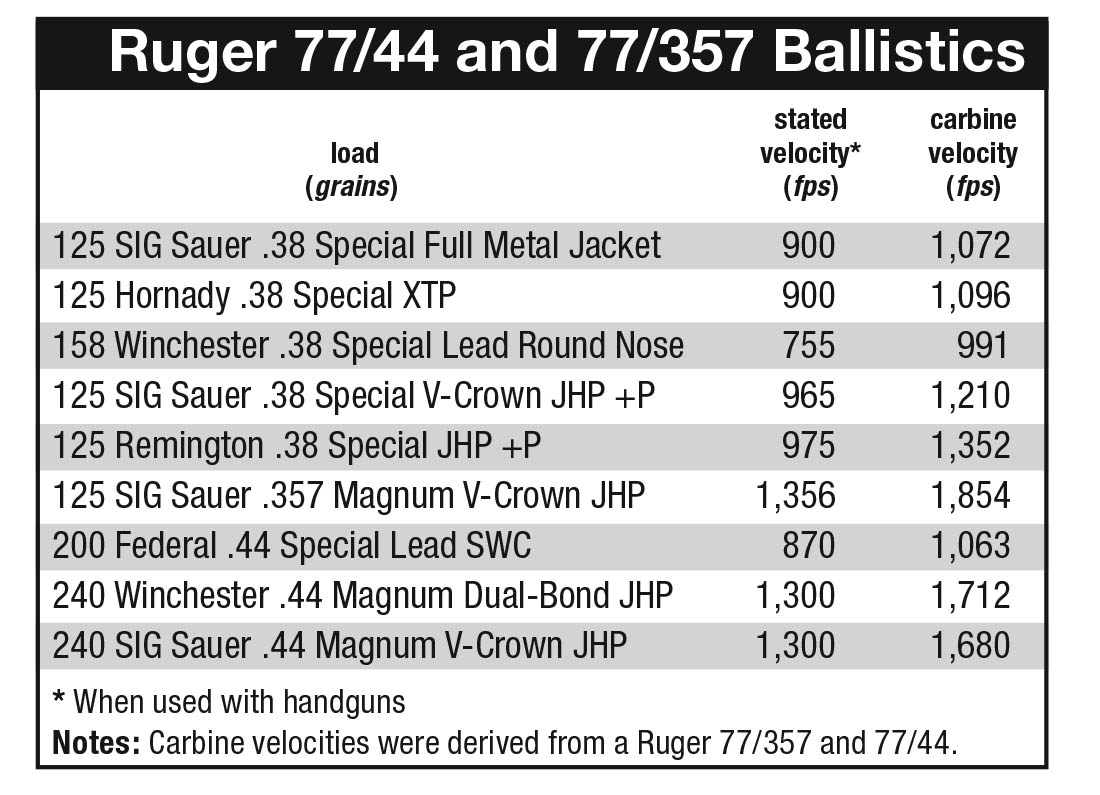

This is the virtue that really makes possible Ruger’s use of such disparate cartridges as the .22 Hornet and .44 Remington Magnum in the short 77s. Each rotary magazine is tailored to a specific cartridge, and while Ruger’s rotary system does not cradle each cartridge as tightly as the Mannlicher’s, it is tight enough. In both the 77/44 and 77/357, you can also use .44 Special and .38 Special cartridges, respectively, for low-cost, low-noise, low-recoil shooting, and the rifles feed them just as reliably.

This is not to say that rebarreling a short-action Model 77 is impossible. For example, there is no reason I can see that a .22 Hornet could not be rechambered to .22 K-Hornet. The cartridges would work perfectly well in the magazine, and you would gain 100 fps.

Ever since buying a 77/357, the thought has haunted me that one could be rebarreled to the .256 Winchester Magnum, which is simply the .357 Magnum necked down; the magazine would work perfectly well. Unfortunately, barrels for the short Rugers are not all that easy to come by, and whenever I’ve suggested the project to a gunsmith, I’ve received nothing but strange looks. Most of them don’t know what the .256 Winchester Magnum is. When you think of it, though, the idea is not far-fetched. The .256 has been ignored from day one, but it still exists as a cartridge, fits into anything that will accommodate the .357 Magnum, and its 60- or 75-grain bullet at 2,400 to 2,700 fps would give the short Rugers a useful small-game cartridge in between the Hornet and the .357.

Given Ruger’s penchant for doing the unimaginable, this seems to me like a natural, and Ruger could likely persuade Hornady to produce ammunition.

Ballistically, the short Rugers open up whole new vistas for handloaders in both the .357 and .44. Broadly speaking, in the longer 18.5-inch barrel of the Ruger carbine, .38 Specials mirror .357 Magnums, and .44 Specials mirror .44 Magnums. The .357 Magnum becomes a reasonable bet for hunting anything up to deer within 100 yards, and the .44 Magnum becomes the deer-and-hog cartridge we are familiar with from the various .44 Magnum lever actions over the years.

Going the other way, lighter .38s and .44s can be used with lead bullets to shoot at steel plates on ranges that would normally prohibit the use of rifles. Used this way, they become first-rate training rifles, especially for women and children who might have difficulty with the weight or recoil of full-sized bolt actions.

Leaving women and children out of it, however, the short Rugers make possible something that can be found with very few “serious” bolt-action rifles: They are unequivocally and unapologetically fun to shoot. You can go to the range with a few hundred rounds of ammunition, set up any target that goes thwang! and have a ball. Guaranteed, if there is anyone else on the range who hasn’t seen the little Rugers before, you’ll make yourself some new pals – wanted or otherwise – in record time. The combination of short rifles and toppling steel is irresistible.

Honestly, the only load I have found with any of the Rugers that has what I would consider noticeable noise or recoil is the full-house .44 Remington Magnum. The others can be shot all day without a hint of discomfort or fatigue.

Since their introduction, the line of short 77s – now called the “77 series” rifles – has expanded, contracted, been discontinued (or suspended) and then reintroduced. There is now a 77/17, chambered for either the .17 Hornet or .17 Winchester Super Magnum. In addition to different calibers, 77 series rifles are available in both blued steel and stainless, with walnut, laminate or synthetic stocks. However, not all variations are available in all calibers. For example, my 77/44 has a camouflage stock, which apparently is no longer available. I never thought I would lament the departure of a camouflage stock, but I really like this one. The 77/17s are available only in walnut or laminate stocks, while the 77/357 comes only in a gray-green synthetic. Like weather in the mountains, though, if you don’t like the variety, give it a few minutes. It’s sure to change.

Gene Hill, that great writer for Field & Stream, years ago offered a very sage piece of advice: “If you find something you like, buy two; they’re sure to stop making it.” My advice to carbine lovers is this: If you see something on the Ruger website you like, buy it now. I’m not saying the company will discontinue it, but the 77/357 and 77/44, especially, are too good to miss.