Parts Rifles

Building "Custome" Bolt Actions on the Cheap

feature By: John Barsness | March, 18

Various definitions of “custom built” include making something designed specifically for a customer, especially “the requirements of a particular person.” With sporting rifles this used to mean a handmade, hardwood stock, usually with other touches often added to the metal, especially the action, and maybe a new barrel.

Today stocks are made of a far wider array of materials, and a custom rifle often means an unaltered factory action fitted with an after-market synthetic stock and a prechambered barrel. Terms such as “customized,” “semi-custom” and “full custom” appear frequently, and “full custom” is often applied to a factory action with an after-market barrel and stock.

This trend started due to mass production. Despite many shooters whining about a lack of “quality” in today’s lower-priced factory rifles, their dimensions are far more consistent than when rifles were all supposedly hand-finished. A major improvement in mass production occurred during World War II, when anything from Garand rifles to Jeeps to B-17 bombers had to be put together as quickly and efficiently as possible. This wasn’t only to get finished products into action, but to make parts as interchangeable as possible, so everything could also be repaired quickly and efficiently.

After the war this consistency resulted in rifles like the Remington 721/722, introduced in 1948, and essentially the early version of the Model 700. Parts were mass produced as efficiently as possible, which didn’t please shooters who were used to rifles like the revered pre-’64 Model 70 Winchester. In fact, many postwar shooters were just as upset by the 721/722 as some of today’s shooters are upset by “affordable” rifles with injection-molded stocks and plastic magazines – and for the same reason: The 721 and 722 were very accurate.

As a result of more precise and efficient manufacturing, the parts of many modern rifles can be mixed and matched to produce what some shooters quite logically call “parts rifles.” But in another sense these are custom rifles, because they are put together for the requirements of a particular person – often by the person who put the parts together.

Just as there are different levels of custom rifles, there are different levels of parts rifles. After World War II plenty were put together by garage gunsmiths using “war surplus” bolt actions, especially 1898 Mausers and 1903 Springfields purchased cheaply through various outlets.

As a result, a thriving industry appeared to serve garage gunsmiths, providing after-market stocks, triggers and barrels. Toward the end of this era I even took part, putting together a few ’98s with prethreaded, prechambered barrels and semi-inletted walnut stocks.

Perhaps the most ambitious was a .257 Roberts built on a Mexican ’98 Mauser action from a 7x57 military rifle, using an Adams & Bennett lightweight sporter barrel and a classic-style, pre-inletted piece of American walnut that I final-inletted, finished and checkered. Back then I supported part of my rifle habit by doing stock work, and the .257 turned out pretty well, but eventually old military rifles became too valuable to tear apart for their actions. The military Mexican 7x57 rifle my action came from cost $85, but today many original military Mausers bring at least 10 times as much.

While some hunters still believe remodeled military actions are better than any commercial action, it makes far more sense to use a newer commercial action of any sort rather than turn old warhorses into serviceable sporters. Considering inflation, many of today’s commercial bolt-action rifles can be purchased almost as cheaply as a war surplus Mauser or Springfield in the 1950s, especially when “pre-owned,” but they can be far more easily mixed and matched by a garage gunsmith with a barrel vise, epoxy-bedding compound and a few screwdrivers.

While vises and wrenches are required for traditional barrel fitting, with the rear end of the barrel firmly screwed against the front of the action, the most common method of home rebarreling involves barrels tightened by a nut on the front of the action – the method used both on AR semiautos and several bolt actions, Savages in particular. This usually requires only a simple hand wrench, with the barrel nut used to adjust headspace. The tools for changing barrels can be purchased for as little as $25.

Home barrel installation is normally accomplished with headspace gauges. These are also inexpensive, partly because they’re often usable for several cartridges. As an example, a .30-06 gauge, like the Clymer I’ve owned for a couple decades, also works for the .25-06 Remington, .270 Winchester, .338-06 and .35 Whelen, as well as several wildcats. (Some people, however, use unfired cartridge cases, including some gunsmiths – not as precise as steel gauges but not exactly guessing either.)

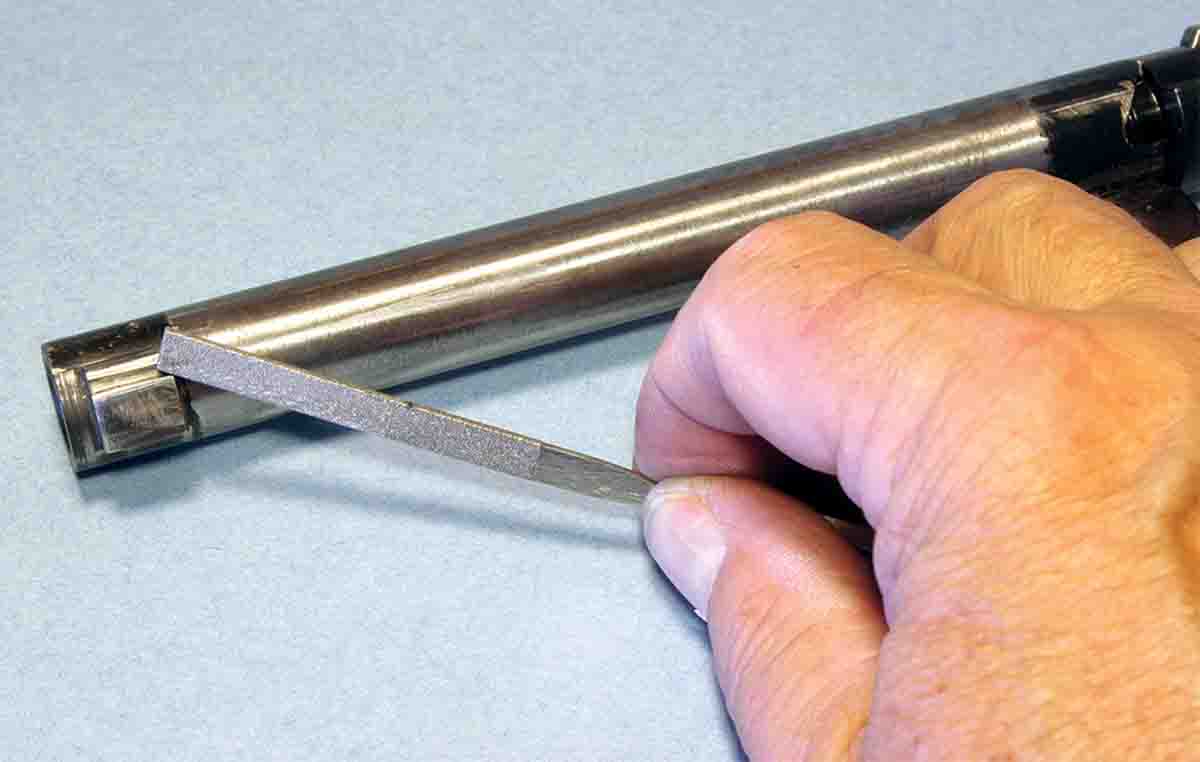

All that is required is to put a “no-go” headspace gauge in the chamber of the barrel, then screw in the barrel until the bolt handle can be closed about halfway, and tighten the barrel nut.

In 2016 I did just that with a Savage Axis, one of the company’s most affordable rifles. The .22-250 Remington was purchased on sale at a local store. At the time, a mail-order company was selling new E.R. Shaw barrels threaded and chambered for the .250-3000 Savage for only $120. It took less than an hour to remove the .22-250 barrel and fit the new .250 barrel, which shoots Nosler 85-grain Ballistic Tips, Barnes 100-grain Triple-Shocks and Sierra 117-grain GameKings into less than an inch at 100 yards.

By coincidence I had a Remington 700 .204 with a shot-out barrel, due to a few years of prairie dog shooting, so I purchased the stainless barrel. The new barrel’s headspace proved to be not only within SAAMI specifications, but so similar that handloads for the old barrel chambered and shot fine. In fact 80 percent of the Remington factory barrels I’ve screwed onto various 700 actions have headspaced within SAAMI specifications, and a long-time gunsmith friend says his experience has been similar.

Today’s stocks are also much easier and cheaper to replace than they were in the heyday of military “sporterizing,” for the same reason factory barrels are abundant and highly affordable: Somebody buys an inexpensive factory rifle to be customized and discards both the barrel and stock. Many discarded stocks are injection-molded synthetics, but while many shooters sneer at such stocks I’ve had pretty good luck with them, often just by screwing them onto my rifle.

Sometimes, however, they require epoxy-bedding plus some work with a round rasp on the forend to make sure the barrel is really free floated, and quite a few shooters spiff them up with spray paint. My friend Tom Brownlee is a parts-rifle addict and has painted a bunch of synthetics in interesting ways, including zebra stripes.

The flood of injection-molded factory stocks also reduced the price of factory walnut take-off stocks, often to $100 or less. The Remington 700 .204 Ruger I re-barreled was originally a Varmint-Target Rifle (VTR) with a triangular blued barrel and dull-green, injection-molded stock, with a broad forend vented with a line of holes. The synthetic stock looked a little weird against the slim stainless barrel, so the Internet revealed a walnut CDL stock for a short-action Remington 700, priced at $100 shipped. When the stock arrived, it turned out the previous owner had epoxy-bedded the recoil lug area, but the stock still bolted easily onto my barreled action. Accuracy actually improved a little, perhaps because of the stiffer walnut, so I didn’t bother rebedding the CDL stock.

Modern computer manufacturing has also resulted in totally finished after-market stocks that often bolt right onto today’s rifles. I’ve had very good luck with wood after-market stocks from several companies, usually without using any bedding compound. Eventually the camouflage synthetic stock on my Savage .250-3000 might have to be replaced with something more in keeping with the cartridge’s classic origins.

My latest parts rifle involved quite a bit of work but turned out to be a great bargain. I had always intended to order a custom rifle from Mickey Coleman, an accuracy gunsmith from Alabama, but in 2014 he suddenly passed. A year later I happened across an ad for a 22-inch stainless Douglas barrel Mickey had chambered for Nosler’s commercial version of the .280 Remington Ackley Improved. The ad also included a long 700 action, though without a bolt or any magazine parts – probably because the seller had purchased a custom 700 bolt and decided to keep it for another project.

The total price was just about the cost of an unchambered barrel direct from Douglas, and I was fresh out of .280 Ackley Improveds. After the package arrived, the obvious first step was acquiring a bolt. New 700 bolts are available from various sources, but in keeping with the bargain theme of parts rifles, I instead called a few gunsmith friends who normally had a few Model 700 bolts on hand. One happened to have a spare long-action bolt and refused to accept any money for it, because the only original moving part still attached to the bolt was the extractor. An ejector, cocking piece, firing pin and spring would have to be ordered, but their total price was less than half of a new bolt.

The headspace, once again, proved to be within SAAMI specifications, so locking-lug contact was tested using a blue magic marker. Both lugs had plenty of contact with the action recesses, so I started looking for a stock.

One Internet site listed an old Remington 700 ADL walnut stock with genuine 1970’s impressed checkering – exactly the same model that came on a .270 Winchester ADL I had purchased in 1974 in Wolf Point, Montana. That .270 proved to be one of the most accurate big-game rifles I’ve ever owned, and the “new” ADL stock was also nicely fitted with a Pachmayr White-Line ventilated recoil pad, also exactly like the one I had fitted to the .270.

The stock’s seller also had a Remington trigger guard he could be willing to part with for a few more bucks. Between the sentimental and practical value of the retro-stock, I decided to go for it. We negotiated a little, eventually settling on $80 for the stock, and a handful of 7mm bullets for the trigger guard, so he could try them in a 7mm-08 he had recently acquired.

Meanwhile the bolt innards arrived. The parts worked perfectly, but the pull of the slightly rusty trigger on the action was erratic. I sprayed the trigger thoroughly with a solvent, and after letting it soak for a while the pull became consistent, but gritty. Luckily, a while back I had purchased a Timney Remington 700 trigger from somebody who really needed $100. Even more luckily, I eventually remembered acquiring it, and after considerable searching found the Timney in a tackle box, along with a bunch of other rifle parts I had mostly forgotten.

The barrel channel of the ADL stock required some light chisel work just in front of the action to perfectly free float the No. 2 Douglas barrel. After epoxy-bedding the recoil-lug area and mounting a scope, my “new” .280 Ackley Improved was ready for range testing. While several bullet/powder combinations grouped well, I eventually settled on the Hornady 162-grain ELD-X with 65.0 grains of Ramshot Magnum, which averages around .5 inch for three-shot groups at 100 yards, and .75 inch for five-shot groups. Not bad for a rifle costing a total of $630!

Saving money is only part of the attraction of parts rifles. The rest is in the search for parts, which often keeps rifle loonies contented during the brief periods when they can’t be out shooting.