Long-Range Shooting Tips and Tools

What Works and What Doesn't

feature By: Brian Pearce | May, 21

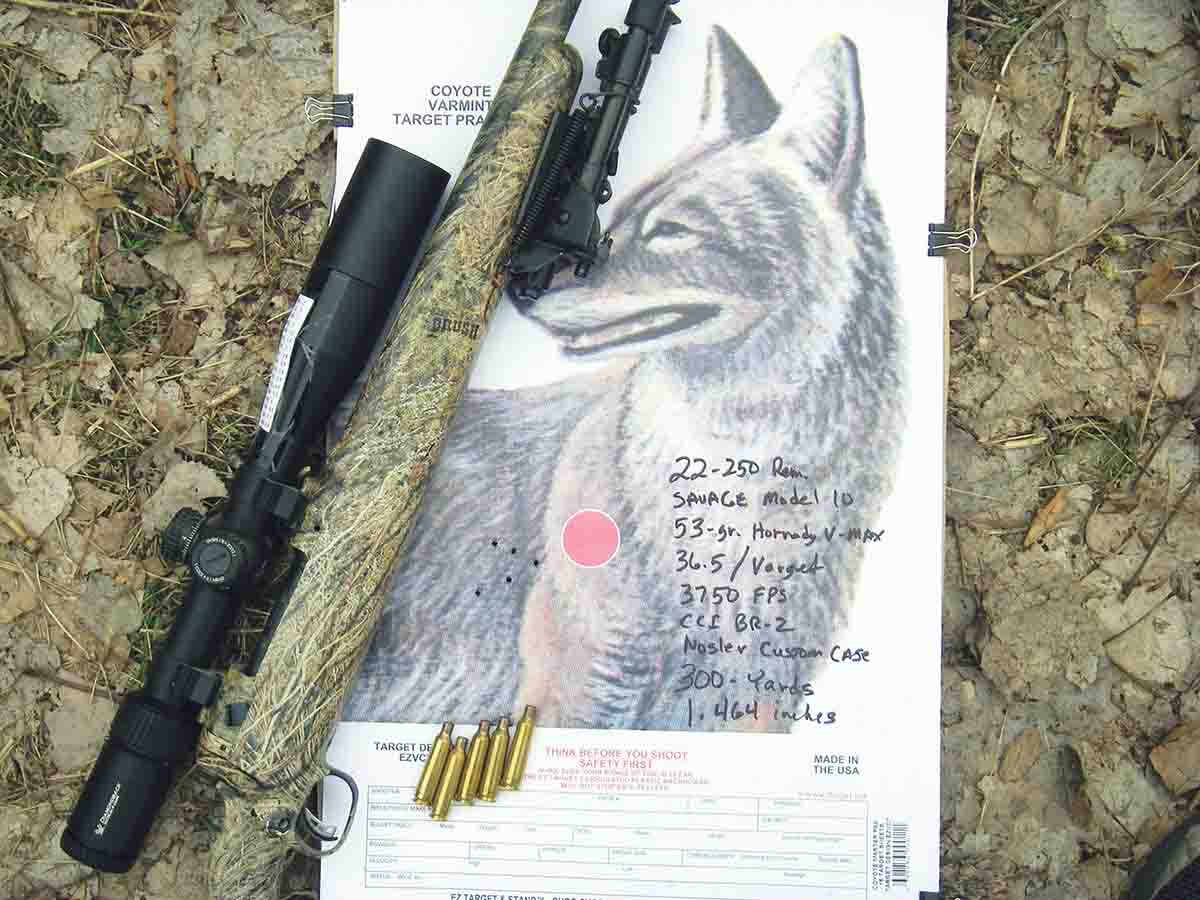

For example, during my teen years I often used an early Remington Model 700 .243 Winchester topped with a 3-9x variable scope to shoot coyotes on our cattle ranch. Before virtually burning the barrel out of that gun, when I could connect with some certainty at 300 to 400 yards, I was very pleased with the rifle, handloads and shooting, but when the distance was moved out to around 500 yards, the hit ratio always dropped, sometimes to the point of hits being much more on the lucky side rather than skill.

The next day was a virtual repeat, but this coyote was in a different field. I heard the bullets’ distinct impact before I heard the rifles’ report. The shot was 613 yards.

These comments are not for competitive long-range shooters, rather they are tips and tools that should help hunters make reliable hits on varmints, pests, predators, etc., in the field and are primarily geared toward the widely popular bolt-action rifle.

An accurate rifle becomes paramount in order to make long shots. It was not that long ago that an out-of-box bolt-action sporting rifle capable of Minute of Angle (MOA) accuracy was something of a rarity, but today many entry-level rifles are capable of groups around .50 to .75 MOA with select factory loads, while top-drawer rifles with carefully tailored handloads can often group under .50 MOA and even .25 MOA or less. Using a consistently accurate rifle will help eliminate long-range variables.

While most modern bottleneck rifle cartridges can offer reasonable long-range performance, certain ones do offer notable advantages. For example, competitors usually favor cartridges designed specifically for top accuracy, boast of low extreme spreads and are mated to fast twist barrels designed to stabilize heavy-for-caliber bullets with comparatively high ballistic coefficients (BC). Velocities are generally preferred to run between 2,700 and 3,000 feet per second (fps), which combined with high BC bullets will stay supersonic out to 1,000 yards and beyond. Properly designed heavy-for-caliber bullets retain higher velocities and buck the wind better at extreme distances.

However, in the field and at practical shooting distances, cartridges and loads that produce higher velocities can offer certain advantages, even if their BCs are lower. For example, competitors know the exact distance to a given target and zero their rifles accordingly before a match. In the real world of field shooting, exact distances can be difficult to determine. Certainly, we use quality rangefinders; however, sometimes the target is less than reflective, especially at longer ranges, and will not give a “reading.” In these instances, we must find a more reflective surface near the target to obtain a reading, such as a rock, tree, etc. However, they are almost never exactly the same distance as the target. Even if the rangefinder will read off the animal, they often move a few yards before putting the rangefinder aside, getting into a locked position with the rifle and the shot taken. Regardless, the measured distance is usually not exact. Cartridges and loads with lower velocities associated with match competition tend to have a comparatively high trajectory. In other words, bullets are coming down on the target at a fairly steep angle and the allowable yardage error is minimal. If the target is just a few yards off, closer or farther than where the shooter is holding, it will result in a miss. On the other hand, select lighter weight bullets pushed to higher velocities often offer a flatter trajectory and have less wind drift at more common field shooting distances of 600 yards or farther.

Changing the load to the 95- grain V-MAX bullet (.365 BC) with a muzzle velocity of 3,300 fps, with a 400-yard hold, hits will occur at 377 and 421 yards, for an error window of 44 yards, which is a notable improvement from the heavy bullet load. With a 600-yard hold, bullets will stay within the 7-inch kill zone at 589 and 610 yards for a 21-yard error window, which again is better than the 143-grain ELD-X bullet. At 800 yards, the error window drops to 12 yards, or 794 and 806 yards, respectively, and is only slightly less than the 143-grain ELD-X bullet.

Now, let’s switch to the 66-year-old .243 Winchester. Using the 108-grain ELD Match bullet (.536 BC) at 2,950 fps, with a 400-yard hold, bullets will stay inside the 7-inch kill zone at 379 and 419 yards, which is a 40-yard error window. At 600 yards, the error window drops to 21 yards (589 and 610 yards, respectively), while at 800 yards, the error window is 13 yards (794 and 807 yards). Switching to the 87-grain Hornady V-MAX (.400 BC) at 3,450 fps, at 400 yards the error window is an impressive 52 yards with bullets staying inside the 7-inch zone at 373 to 425 yards, respectively. At 600 yards, the error window is 25 yards with hits being made at 587 and 612 yards, respectively. Moving out to 800 yards, the error window is 14 yards with hits between 793 and 807 yards.

It is noteworthy that unlike hitting a steel target that is the same size as a coyote at a known 800 yards, along with the huge advantage of having a few spotting practice shots, taking coyotes at 800 “field” yards and beyond with any degree of certainty on the first shot is extremely uncommon, even for the best rifleman in the world. Rather, the majority will be taken inside 600 yards. In addition to the rangefinder misreads previously mentioned, coyotes are always shifting, jumping, moving, etc. Many times I have ranged the distance, read the wind and locked onto a coyote, then fired what should have been the perfect shot, only to have “Mr. Coyote” move just a millisecond after the trigger broke, and missed.

Regardless of the cartridge chosen, it should offer ultralow extreme spreads to prevent vertical stringing, which results in complications at long range.

While factory loads are better than ever, they should be carefully tested for accuracy and extreme velocity spreads. Furthermore, factories often change the powder type and/or charge with a given load. If ammunition lot numbers are changed, there is a good chance that the new lot number will perform differently, which can change point of impact. Skilled handloaders can develop precision loads tailored to a given rifle and can outperform factory loads (accuracy and velocity). Regardless if the ammunition is factory loaded or handloaded, it should be tested for accuracy at the maximum distance that it will be used. Its velocity should be checked at similar elevations where the hunt will take place and checked at different temperatures. A knowledgeable handloader will usually select propellants that will be least sensitive to temperature changes, humidity, etc. A chronograph is a must to fully evaluate ammunition.

Ballistic drop charts are useful information; however, they are often less than precisely accurate. Therefore, it is strongly suggested to check the load and rifle in the field at extended distances, or the longest shot that will be attempted, to establish point of impact references. This will help the shooter better establish bullet drop, spin drift and other variables. Based on that testing, a custom drop chart can be created that is generally attached to the rifle (taped to the scope or stock) that will correspond with both holdover and scope dialing.

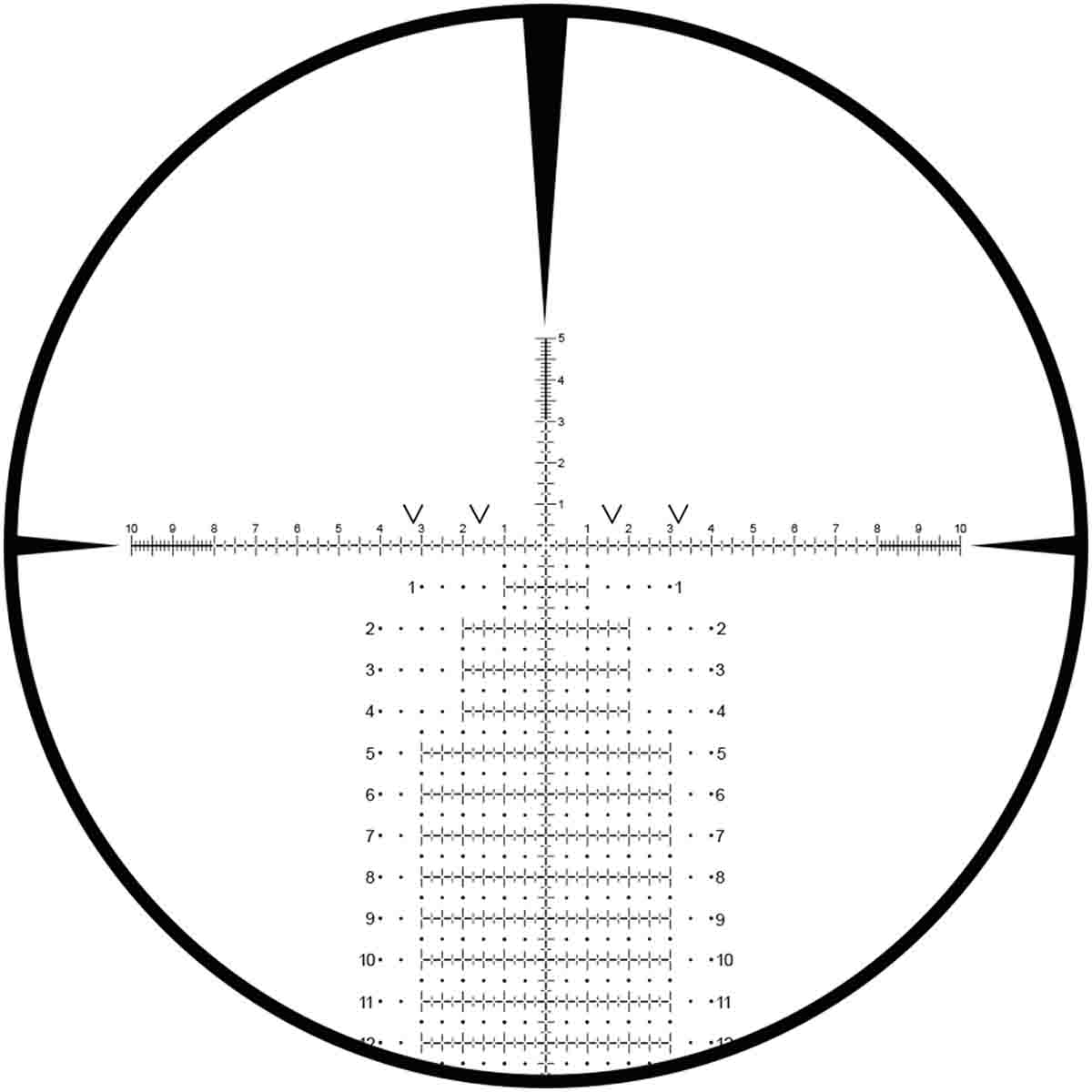

With this thought in mind, when selecting a scope, choose one that is of high quality and has enough internal adjustment for long shots (usually found on scopes with a 30mm or larger maintubes) and preferably is fitted with zero stops. Select a reticle that offers precise holdover reference points. Scopes featuring a front focal plane reticle are preferred by myself and are becoming hugely popular, as they are simpler and offer many advantages.

Naturally, the rifle stock should give proper fit to the shooter, including length of pull and cheek weld, but it should also be designed to work in multiple shooting positions that may become necessary in the field. Shooting prone is an excellent position in the field, although it is not always possible due to terrain, vegetation, etc. While target stocks are excellent for this application, they are less than perfect when used in other positions often required in the field. From a practical standpoint, a stock must be suitable for shooting prone with a bipod, kneeling, sitting, resting over a backpack, over a fallen tree and even offhand. A classic-style stock with a high comb and semi-beavertail forearm that accommodates a detachable bipod is still a great general purpose field stock. While some rifle and stock manufacturers offer classic stocks with a negative comb that work very well, an adjustable cheekpiece (or comb) adds versatility and is a top choice for general field use.

While there are many products that aid the long-range shooter, the practical side of me tends to keep equipment simple and minimal, all of which helps to keep the weight of my pack down. First is a quality rangefinder. It must not only be accurate, but return fast readings, as time is often of the essence to get locked onto a coyote and make the shot. While doping the wind is a learned skill, high-quality optics can help see and estimate downrange wind speed and direction. Nonetheless, a wind meter is still a very useful tool, such as those offered by Kestrel.

Skills that should be continually honed include shooting from a variety of positions, including prone with bipod, resting over a backpack, a log, sitting, kneeling and even offhand. If using a bipod, whether the bipod is preloaded or not, the real key is to be as consistent as possible and repeatable with each shot. It is noteworthy that sighting-in using a preloaded bipod will usually result in point of impact changes when firing from other positions. Field surfaces vary enough that duplicating the preload pressure is difficult. For these reasons, many shooters don’t preload a bipod.

Trigger control should be practiced with dummy cartridges, with emphasis on follow-through, then move onto live ammunition. The value of a good trigger pull with minimal after-travel will quickly become apparent. Good conditioning will usually help to lower the heartbeat rate and control breathing. Timing shots between heart beats will help with precise bullet placement. With the correct rifle, cartridge, load, optics and skill, making the perfect long shot in the field can be much more than just luck.